/ The right to education is acknowledged in Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Right to energy toolkit ● Publication

Making the case that access to sufficient, affordable energy underpins the right to a dignified life, a new report from the ENGAGER-COST network offers guidance on elements to consider in a rights-based perspective – and practical approaches for moving towards it.

Emphasising the need for people-centric energy policy, the Right to Energy Toolkit highlights the ‘duty of responsibility’ held by public authorities to engage all stakeholders in ensuring all citizens can afford sufficient energy and participate in energy democracy.

Launched during the opening session of the International Energy Poverty Action Week (21 Feb 2022), the Toolkit offers perspectives for developed and developing countries.

What do we mean by a ‘right to energy’?

Contributors to the ENGAGER-COST Right to Energy Toolkit highlighted two overarching principles that are fundamental:

- That all individual humans have equal opportunity to enjoy certain rights and entitlements to be able to enjoy access to energy services necessary for health, well-being, social inclusion and full participation. Energy is vital for a dignified human life.

- That others, especially the State, have duties to ensure rights for everyone, equally and without discrimination. A myriad of related concerns can be identified, which largely fall under three overarching themes: access, affordability and energy democracy.

Recognition of basic rights and entitlements implies corresponding duties to respect, protect and fulfil such rights. The State, from a perspective of human rights, holds primary responsibility to create enabling conditions for the full realisation of rights. Public authorities must therefore design coherent policy frameworks that contribute to progressive realisation of the right according to maximum available public and private resources. They must also address and remedy any discrimination or disadvantage, and guarantee monitoring and oversight and access to justice.

Energy access for a dignified life

Human rights are often linked to the concept of a ‘dignified life’ (or ‘life with dignity’) or to the ‘capabilities approach’, all of which emphasise establishing legal frameworks to ensure all individuals have equal opportunities to reach their potential and aspirations.

The concept of a right to energy is noted as early as 1981, when the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women included the ‘right to electricity’ for rural women. Forty years on, while such a right is specified in some existing legislation, often it is not adequately upheld. One relevant example is the EU Pillar of Social Rights (2017), which includes energy among the right to essential services. However, as this charter is not yet legally binding, it does not empower people to take action if their right is not being upheld.

Human rights are also directly related to non-discriminatory practices, which are, in turn closely tied to equality, equity and vulnerability. Access to modern energy is vital to achieve the first two and reduce the last. This implies the need for governments to undertake efforts to identify which individuals or groups, because of particular characteristics, are vulnerable or are being treated in a discriminatory manner when it comes to energy – and to prioritise such groups in efforts to begin closing massive gaps in equality and equity. The Toolkit also recognises that sources of vulnerability can be physical conditions, socio-economic differences and/or contextual considerations.

Getting specific about ‘accessible’ and ‘affordable’

The right to energy, under the approach put forth by ENGAGER-COST, highlights a key overarching principle: access to socially and materially necessary minimum energy supply while ensuring that related costs do not constrain a person’s ability to meet other basic needs.

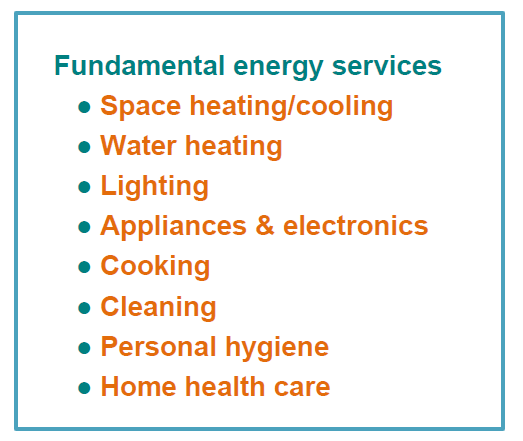

The report balances information about what might be considered a ‘minimum level of energy access’ in diverse contexts with the need to ensure both quantity and quality of supply such that people can enjoy fundamental energy services.

Helpfully, the Toolkit offers five indicators that can be used to capture people’s minimum energy needs:

- a minimum set of energy services

- a list of relevant appliances

- a minimum level of energy efficiency

- a minimum level of quality of supply (i.e. regular)

- minimum levels of kilowatt hours of electricity and/or cubic meters of gas or other fuels (quantity of supply).

It also notes that for such services to be affordable, both energy supplies and efficient appliances need to be universally affordable.

In a nod – or perhaps a challenge – to recent progress in boosting electrification levels in developing countries, the Toolkit also sharpens the focus from national statistics to daily reality at the household level. Individuals, it says, must be the ultimate ‘unit of concern’ when it comes to energy access. Energy policy and legislation need to be established with respect to the diversity of resources and personal needs.

Putting the right to energy into practice

As noted in the Toolkit, in current human rights law ‘energy is present but not yet protected’ – i.e. the right is not explicitly recognized in law. In response, the Toolkit sets out principles for establishing legislation and policy frameworks that empower citizens and their representatives to exercise their right to energy, in terms of both demanding access to supplies and services and participating in energy decision-making. Short sections cover three key areas:

- Energy democracy for people-centred policies aims to give people affected a voice in determining ‘how’ the right to energy will be respected, protected and fulfilled.

- Consumer protection and advocacy, including to address infringement of rights highlights the vital and complementary roles of activists, ombudspersons, consumer groups and the academic community in raising awareness and building political momentum.

- Governance and delegation of responsibilities returns to the lead role of states and regulators in setting up policy and regulatory frameworks that uphold the right to energy – including determining which other entities must be held accountable, and in what ways.

In Spain, the Alliance against Energy Poverty (Aliança contra la Pobresa Energètica or APE) organises protests to fight for access to basic supplies (i.e. energy and water) as a fundamental human right. They build a critical mass for advocacy through coalition-building among social and environmental organisations concerned about energy poverty, housing and evictions. Photo courtesy of Aliança contra la Pobresa Energètica

As noted by Sustainable Development Goal No 7 (SDG7) – which calls for universal access to clean, affordable and sustainable energy – eradicating energy poverty is a global concern. But each country must consider local conditions (including diversity of energy sources) and challenges, and act accordingly. While relevant policies may be regional, national or local in scope, they all must fully consider the role of different actors in addressing energy injustice. In a handful of case studies, the Toolkit provides examples of effective actions.

The ENGAGER-COST Toolkit can serve as a reference for policymakers, stakeholders and energy communities worldwide.